San Francisco Transportation History

From “How America Can Bike And Grow Rich, The NBG Manifesto“

To understand transportation in San Francisco, it is is important to understand its early development in relation to colonial America. Its unique geography is another factor that has changed the way its people move about. When you also consider the natural disasters that have altered its course, you will see what has given rise to its forward thinking ways as a leader in the ways people move themselves about. Its present return to its more bike-centric ways is how San Francisco continues to set the lead for other cities to follow.

San Francisco, the 13th largest city in the US at 825,863, represents the seven mile by seven mile (49 square miles) tip of a peninsula. It stands between an enormous bay, 1600 square miles in size, and the Pacific Ocean. Despite the fact that the East Coast had been settled for almost 130 years, San Francisco would not become known to Europeans until 1770. Oblivious to one another, while the colonists were busy getting the Declaration of Independence signed, only five days before that document became official, on June 29. 1776, Spanish Franciscans who had traveled north from Mexico, founded Mission San Francisco de Asis, their 6th of 21 California Missions.

Located at what is now 16th and Dolores streets, a little less than three miles up Market Street from the waters of the San Francisco Bay, the mission is also referred to as Mission Dolores. It was at this spot that a little lake called Lago de los Dolores once defined the local geography, Even though the lake has long since disappeared, the name Mission Dolores continues today.

Just as the religious center’s waters began to vanish, so did its people. In all of California, until 1848, in the 78 years of Spanish and Mexican control, the native Indian population declined from about 300,000 to 150,000. Mission Dolores, where there were considerable problems with disease, was one of the biggest contributors to this nightmare.

Outside the mission, largely because its weather was not favorable, San Francisco grew slowly. So slow that in 1847, the year before it became free of Spain it boasted only 459 residents. The 1849 discovery of gold one hundred miles away changed all that. By December of that year, its population had swelled to 30,000. And it kept growing and growing.

By 1870 San Francisco, at 149,473 people, had become the tenth largest city in the United States. Everywhere one looked there were hotels, restaurants, parks, churches, synagogues, schools, libraries and academies. It was also in 1870 that the city approved the $801,593 needed for the 1,013 acres of barren land referred to jokingly as “The Great Sand Bank” that would become Golden Gate park. When the building of the park began on what was also called “Sand Francisco” it was called the greatest horticultural experiment of all time.

Six years later, in 1876, word has it that the first bicycle came to San Francisco from Paris. By the 1880’s, HiWheel bicycles, the first bicycles of the day, were ubiquitous in Golden Gate Park. So much so that they their informal races on a horse racing track there, a mile and a quarter mile straightaway, called Speed Road, caused much friction at City Hall. The cyclists were well enough organized back then that they formed, in 1878, the San Francisco Bicycle Club, second bike club in America, and successfully campaigned for their own path along what is known now as JF Kennedy Dr. Until 1904 when cars were allowed into the park, their only competition for use of the park’s many paths had been people and horses.

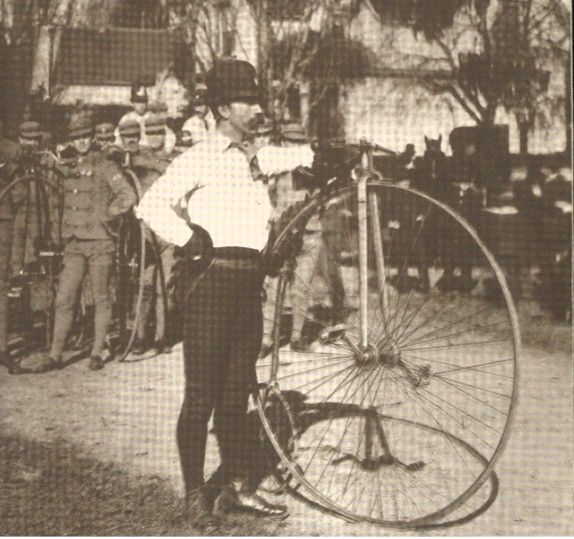

It was in and amongst this setting, in 1884, that a 30-year old man named Thomas Stevens began a two-year bike journey around the globe. Before he left, however, he polished the skills he would need to ride his 50-inch wheel in Golden Gate Park.

While in transit, his regular reports from the road in Harper’s Weekly an influential and widely read magazine in that time period, expanded consciousness for people all over the world and established San Francisco as a beacon of hope for achieving the impossible once his ride was complete. Upon his return, on Jan 3, 1887, the new bike club that formed while he was away, the Bay City Wheelmen (BCW) joined the influential San Francisco Bike Club to receive him.

Thomas Stevens upon his return to San Francisco

In fact. It was the BCW that would go on to build the bike racing track at 8th and Market, very near City Hall, that produced a race that drew 20,000 spectators in 1893. In a city filled with high priced bikes that only the well off could afford, its many bike shops became an economic force that could not be ignored. In endeavoring to spread the craze that bad erupted in their city to a larger market they commissioned a map of the bike roads for the entire state that would go on to become cutting edge.

When by the 1890’s bicycling was made easier for women and more affordable for the masses by the smaller wheel, diamond-frame safety bike, even more bikes flooded the streets of San Francisco. Even the city’s major newspaper, the San Francisco Chronicle knew that the city was a leader in the two-wheel revolution, when in 1905 Ida L. Howard wrote “When San Francisco was Teaching America to Ride a Bicycle”.

A year later, by 1906, San Francisco was filled to the brim in other ways as well. It had five daily newspapers and half a dozen others in foreign languages, 42 banks and 120 places of worship. It also had 3,117 places where liquor was sold. Just as booze flowed freely, so did money. In 1906, the U.S. Mint at Fifth and Mission streets was the largest in the world, and in its vaults was 222 million dollars in gold, one-third of the country’s gold supplies. Known as the Paris of the West, at 410,000 people, it was the largest city west of Chicago when disaster struck.

On April 18, 1906, an earthquake several hundred times more powerful than the atomic bomb that destroyed Hiroshima rocked San Francisco. And yet it was the fire that resulted that did most of the damage. The inferno that devastated San Francisco was twice the size of the legendary Chicago fire of 1871 and six times the size of the London fire of 1666. It burned for four days.

In all, 28,188 building were destroyed over an area, the heart of the city, 4.7 square miles in size. While 225,000 people were left homeless, most of whom moved to the East Bay cities of Oakland and Berkeley, most never to return, some number between 500 and 3000 died as a result of this horrible tragedy.

The quake and fire also expunged its nascent bike movement so as it rebuilt at a feverish pace (in three years time, an amazing 20,000 new buildings had been erected) the only homage it paid to its rich bicycle heritage was the Polo Fields bike racing track that had already been approved for construction before the Quake hit.

To show off the new city that had emerged, in 1909 it threw a three day party called the Portola Festival. By 1910, Angel Island, nearby in the San Francisco Bay had opened to immigrants. Like Ellis Island in New York, it processed the entry of many boat loads of people from many different parts of the world. Most of these new Americans ended up in San Francisco.

To move all the new people that were coming to it around, San Francisco also worked hard to update its transportation infrastructure. The legendary Cable Cars that had been helping people get up some of the steepest streets in the world since 1873 and had grown to as many as 15 lines had already begun to find themselves in competition with electric street cars with overhead wires. When the quake destroyed 117 cable cars and a lot of track, the city fathers yielded to the United Railroad company which had been saying since 1892 that its line powered buses cost less to build and were even cheaper to operate. By 1912, only eight cable car lines remained of which the three that are still active today are only for the purposes of tourism.

San Francisco kept marching forward and by 1915, only nine years after it had been reduced to ruins, San Francisco threw a world’s fair called the Panama Pacific International Exposition. In a part of town near the Golden Gate Bridge, called the Marina district, it constructed a fantastic city of domes and pastel-colored towers. By the time this grand expo was complete, in the eyes of the world, San Francisco was seen as having fully recovered.

In the promotion that preceded this event, it was the Can Do spirit they spread that caught the attention of Carl Fisher. He determined that he would build a highway for cars to the San Francisco celebration. It would travel from Times Square in New York to the Palace of the Legion of Honor in Lincoln Park in San Francisco. Though one actual roadway that made this connection was never built, those roads that were called into service for this, all celebrated the Golden City as their destination.

At its harbor lay the terminus that would receive all of this attention. While ferry boats had been busy transporting people across the Bay from Oakland since 1850, it was the Ferry Building, completed in 1898, that made this process efficient. And luckily for San Francisco, along with the rest of its harbor, it survived the Great Quake and Fire. As its port received the goods from all over the world it would need to rebuild itself, the Ferry Building also brought in the people that would do the work that was needed as well as all those who would soon come in on Fisher’s “highway”.

And most came on foot. While car ferries would not move automobiles and their passengers from one side of the Bay to the other until the 1920’s, the lion’s share of San Francisco water arrivals took advantage of the city’s ubiquitous trolley lines. Even after the railroad companies built ferries to carry automobiles, most still came without a vehicle.

One such ferryboat, the Eureka, for example, which was the biggest and fastest on the globe when it was rebuilt after the first World War so that is could carry cars, still moved far more people than it did vehicles. At 295 feet long, it transported 120 automobiles. And yet as it did, it still moved 2,300 passengers from one side of the Bay to the other.

According to the National Park Service, the Ferry building was once second only to London’s Charing Cross Railway Station as the busiest passenger terminal in the world. And yet the San Francisco Bay Bridge changed all of this. But it took a short while to wean people off the extremely efficient ferry/trolley system that defined San Francisco. For example when the bridge opened in 1936, the toll was 65 cents each way. And yet bridge officials had to lower it all the way down to 25 cents per direction just so they could compete with the Bay’s beloved ferries

Even though the 8.5 mile bridge that connected with Oakland, an engineering marvel of notable proportions when it opened at the end of 1936 did marginalize the Ferry Building, it still brought most of the people it carried to the city without their automobiles While it’s top deck was reserved for vehicles, half of its bottom deck was used by electric commuter trains until 1958 when cars and trucks took over the entire water crossing.

For the next 14 years there were no trains between San Francisco and Oakland and the rest of the populous East Bay. During this time, AC Transit buses carried many tens of thousands of passengers over the bridge on a daily basis. It wasn’t until 1972 that the connection between San Francisco and Oakland was once again at the leading edge. When BART (Bay Area Rapid Transit), the world’s first computer controlled heavy rail transit agency, built an under the bay tube, San Francisco’s visitors could once again arrive there in style. One of history’s most outstanding civil engineering achievements, its 3.5 mile long bore plunges 135 feet below the Bay making it the longest and deepest vehicular tube in the world in service today.

Besides its connections to the East Bay, the San Francisco/Oakland Bay Bridge, one of the busiest in the world, at 280,000 vehicles a day and BART which brings almost half of its daily ridership of 325,000 people to the city, on the West Bay, there are two freeways and passenger rail, Caltrain, that connect it to San Jose and all the peninsula cities in between This as the legendary Golden Gate Bridge connects it to the North Bay counties of Marin, Napa and Sonoma.

In sum, all of this leads to a 21.7% increase in population during the weekdays in San Francisco. The 168,000 new people this represents often end up high above the city in the many high rises that make up the city’s ever changing skyline. A few thousand even get to them on bikes. Outfitted with rail cars that hold as many as 32 bicycles on each of the lines it runs, Caltrain is the most heavily used bicycle commuter railroad in the world.

And thanks to a city full of green, forward thinkers, San Francisco is becoming more and more poised to process all the added bicycle travellers these and other transportation venues will soon be bringing to it. In the not too distant future, cyclists from the East Bay who are now able to take their bikes on a rebuilt Bay Bridge to Treasure Island will be able to ferry the rest of the way in to the city. From the Car Free city of 20,000 people that is expected to emerge on the island that separates the two water crossings, by 2020, as we will touch on when we talk about our trip to Oakland, bridge riders will soon be able to take a ferry to the iconic Ferry Building. As Caltrain keeps adding bike cars to its lines and more and more bikes come in over the Golden Gate and on ferry boats, this city will continue to rise from the ashes of a car centric way that once almost choked it to death.

It wasn’t until the Loma Prieta Earthquake of 1989 inspired it to demolish a freeway blocking it from the proud source of its 1906 salvation, the Ferry Building, and its prized waterfront, that change began to occur. When, in 1991, the Embarcadero, nearly a mile of two thick lines of concrete that stood 70 feet tall and 52 feet in width came down, a new San Francisco was born.

Completed in 1959, the ugly freeway that connected from the Bay Bridge, once was planned to extend through Fisherman’s Wharf where it would turn inland at Aquatic Park on its way then to the Golden Gate Bridge. It wasn’t until 1973 that visionary Mayor, Joe Alioto led a movement that got the state to cancel it, that any more of the destruction it would bring, stopped looming over San Francisco.

Even though it had been stopped a mile short of what is still one of the city’s most popular tourist meccas, Fisherman’s Wharf, the concrete monolith that remained still divided San Francisco between environmentalists who wanted it torn down and Chinatown business leaders and their supporters. The merchants thought the customers it brought them would not want the bother of city streets to get to them. It wasn’t until a 15 second trembler shook the city to its core, making the eyesore freeway unsafe, that city officials finally had the courage to remove it.

And in 1991, when they did a whole new waterfront began to emerge. The city had taken a symbolic quality of life stand for itself. It would demand that passers by slow down and take a look. Just as it refused to be a way point to be stormed through for travelers headed to destinations north or south of it, it also seemed to be saying to its residents and work force population that they all need to slow down as well and smell the San Francisco roses.

And green transportation has been on a roll ever since. Where once there was the Embarcadero Freeway, light rail connects the Giants baseball park and nearby Caltrain with Fisherman’s Wharf three miles away. Along this stretch, there are also bike lanes and a wide sidewalk right next to the waters of the Bay. On the way, one passes under the Bay Bridge hundreds of feet above and by the Ferry Building which sits at the base of Market Street and where San Francisco does its business with the world.

Bicycle activists have played a big role in San Francisco’s green resurgence. When the world’s first Critical Mass bike rides monthly began to leave from Justin Herman Plaza on September 25, 1992, a gathering area that arose from the ruins of the Embarcadero Freeway in front of the Ferry Building, a voice for cyclists began to emerge. When thousands upon thousands of bike riders took over the city’s streets to demonstrate for safer cycling, city leaders began to listen.

Led now by the San Francisco Bike Coaltion, bicycles are an important part of city policy as well as its politics. Over the last ten years, many miles of bike lanes and other infrastructure have emerged. So much so that the League of American Bicyclists has recognized San Francisco as one of its highest ranking bicycle friendly cities.

While there is a tremendous amount of work still to be done, the city has come a very very long way from a time not so long ago when the only safe place to ride a bike was on the off road pathways of Golden Gate Park. For the half a century that cars and trucks ruled the streets all the way to the gutter’s edge, San Francisco was a scary place to move oneself about on two wheels. Thankfully, the city has awakened from the nightmare cars once foisted upon it. And as bicycles help it restore the luster that once made it the Paris of the West, more large American cities will follow its lead as the National Bicycle Greenway becomes an important way to reach all of them.